It is good to be reminded, too, that the mood and spirit of the circle was not remotely radical but rather cautiously reactionary and happily militaristic: the alternative to Uranian love was not socialism but Catholicism, of the kind to which Wilde himself succumbed in the end.

These men were inside the closet, certainly, but it was a bigger and better panelled one than many before or since-and a closet that big and that well panelled is really more like a private club.

Proust remembrance of things past serial#

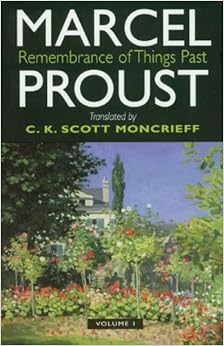

The Wilde circle persisted, more or less openly Uranian, though less expansively self-confident, and came to produce respectable figures such as Moncrieff’s intimate friend Edward Marsh, who was Winston Churchill’s private secretary, and who was hardly “out,” but was, in his serial infatuations, not exactly in, either. It’s frequently said, in popular literature, that after Wilde’s imprisonment the gay literary establishment fled or was frightened into silence, but judging from the evidence assembled here, and in other memoirs of the period, that isn’t quite so. Moncrieff, who was Uranian, as the self-designation was then, emerged from the élite boarding school Winchester College and Edinburgh University into that strange half-lit, prewar world of London homosexuality after the Wilde trial. Scott Moncrieff, Soldier, Spy, and Translator.” And though it occasionally makes one wish that the old form of the brief life would come back into fashion (Moncrieff was an interesting man who led an exceptional life, but he was not that interesting nor that exceptional) the book still helps us see how someone who was not even particularly expert in the original language managed to make a great French book into a great English one. The first full-length biography of Moncrieff is now out, written by Jean Findlay and bearing the cumbersome title “Chasing Lost Time: The Life of C. That Moncrieff called Proust’s book “Remembrance of Things Past,” borrowing from Shakespeare, rather than anything close to a literal rendering of the title “In Search of Lost Time,” is typical of what the translation’s detractors kvetch about to this day. Proust, though many a stiff body is found on the lower slopes, with the other readers stepping over it gingerly.īut the ease of Moncrieff’s translations also started a fistfight, ongoing, about whether his Proust is Proust, near Proust, Anglicized Proust, or not Proust at all. John Middleton Murry, in an early review, wrote, “No English reader will get more out of reading ‘Du cote de chez Swann’ in French than he will out of reading ‘Swann’s Way’ in English,” and amateur book readers, for whom other works of mega-modernism-“The Man Without Qualities,” or “Buddenbrooks”-remain schoolwork, still read Proust. Mostly thanks to Moncrieff, Proust is part of the common reader’s experience in English. Newly published volume by newly published volume, working almost as a simultaneous translator, Moncrieff inserted Proust into the English-speaking reader’s consciousness with a force that Proust’s contemporaries in continental languages never really got. Scott Moncrieff (1889-1930), whose early-twentieth-century English version of Marcel Proust’s masterpiece, “À la Recherche du Temps Perdu,” has been a classic in our own language since the day of its first publication.

A few translators’ names are familiar to the amateur reader-we know about Chapman’s Homer, through Keats, and Richard Wilbur’s Molière is part of the modern American theatre-but mostly translators struggle with sentences for even less moment (and money) than other writers do. The art of translation is usually a semi-invisible one, and is generally thought better for being so.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)